An imposing National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa) probe is due to lift off on Monday on a five-and-a-half-year journey to Europa, one of Jupiter's many moons, to take the first detailed step toward finding out if anywhere else in the solar system could support life.

The Europa Clipper mission will allow the US space agency to uncover new details about the moon, which scientists believe could hold an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy surface.

The liftoff is scheduled for "no earlier than" Monday, from Cape Canaveral in Florida aboard a powerful SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket, Nasa said in a statement.

"Europa is one of the most promising places to look for life beyond Earth," said Nasa official Gina DiBraccio at a news conference last month.

The mission will not look directly for signs of life but will instead look to answer the question: Does Europa contain the ingredients that would allow life to be present?

If it does, another mission would then have to make the journey to try and detect it.

"It's a chance for us to explore not a world that might have been habitable billions of years ago," like Mars, Europa Clipper programme scientist Curt Niebur told reporters last month, "but a world that might be habitable today, right now."

The probe is the largest ever designed by Nasa for interplanetary exploration.

It is 30 metres wide when its immense solar panels — designed to capture the weak light that reaches Jupiter — are fully extended.

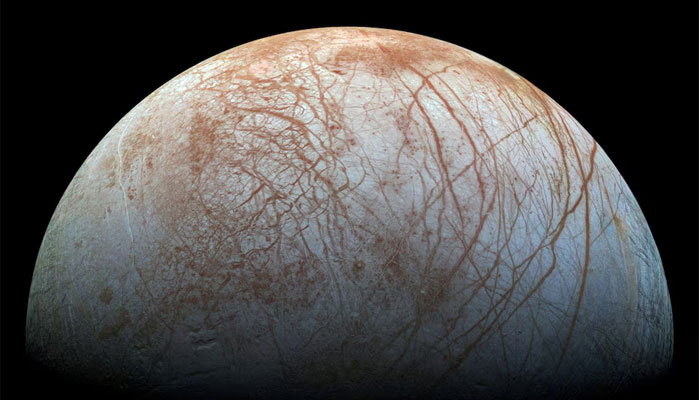

While Europa's existence has been known since 1610, the first close-up images were taken by the Voyager probes in 1979, which revealed mysterious reddish lines crisscrossing its surface.

The next probe to reach Jupiter's icy moon was Nasa's Galileo probe in the 1990s, which found it was highly likely that the moon was home to an ocean.

This time, the Europa Clipper probe will carry a host of sophisticated instruments, including cameras, a spectrograph, radar, and a magnetometer to measure its magnetic forces.

The mission will look to determine the structure and composition of Europa's icy surface, its depth, and even the salinity of its ocean, as well as the way the two interact to find out, for example, if water rises to the surface in places.

The aim is to understand whether the three ingredients necessary for life are present: water, energy and certain chemical compounds.

If these conditions exist on Europa, life could be found in the ocean in the form of primitive bacteria, explained Bonnie Buratti, the mission's deputy project scientist.

But the bacteria would likely be too deep for the Europa Clipper to see.